He came into the world seven hours ago but he’s alert, wriggling in his cot.

Mum Jennifer Hemingway, a senior staff nurse in the neonatal intensive care unit, gazes at new born son Frederick Thomas, born a few minutes before 3am.

Now just 10am, Frederick Thomas, likely to be known by his family as Freddie, is about to be screened for hearing problems.

“We try to screen all the babies in the maternity unit before they go home,” says senior screener Allison Bird, placing a tiny soft-tipped ear piece in his ears while she measures a response. “It’s important that any issues are picked up early.”

Frederick Thomas is one of 6,500 babies screened every year by the eight-strong neonatal hearing screening team at Hull Women and Children’s Hospital.

Babies born at home or at Scarborough and Scunthorpe hospitals but whose parents have an East Riding GP are also seen by the team at clinics at Women and Children’s, Goole, Beverley and Bridlington.

The Hull team has achieved a 99.7 per cent pick-up rate, one of the best in the country, after the national programme was launched here in 2003.

One to two babies in every 1,000 born have permanent hearing loss in one or both ears. For babies spending more than 48 hours in intensive care, it’s one in 100.

Identifying problems early on can ensure the child is supported in developing language, speech and communication skills.

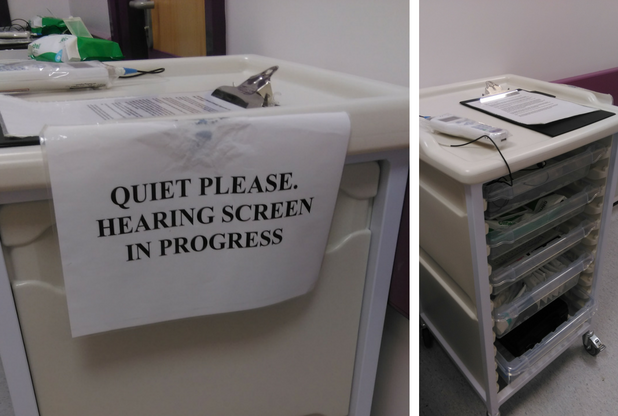

The team need silence to conduct their tests

Neonatal hearing screeners Kristina Purdon, Marcel Khan and Kath Bagshaw are on duty with Allison today at their office on Rowan Ward.

Most of the team has been together since the start so there’s easy camaraderie and work is ticked off with minimum fuss. Everyone knows what to do, is aware of their role and the support is there if they need it.

Dressed in green trousers and white tunic tops, they share out the list of babies to be seen. There are 19 today, a typical day.

Some babies have just been born and will be checked before they go home while others are special care babies on NICU. Premature babies cannot be tested until they reach 34 weeks’ gestation.

The team wait for babies to be settled, often just after feeds or while they are asleep, as wriggling babies can make the reading inaccurate.

For the first screening test, Allison and the team fit the ear piece into the babies’ ears connected to an automated handheld device measuring otoacoustic emissions (AOAEs).

When a soft clicking sound stimulates the cochlea, the outer hair cells vibrate and the vibration also produces a sound that travels back through the ear to the ear piece as a response. If there’s no response, the test is repeated.

Clear responses are not always possible, given how soon the tests are carried out after birth. A lack of response can mean the baby was unsettled, there was background noise on the ward or the baby had fluid in its ear. But it can also be a warning sign of hearing problems.

Frederick Thomas’s right ear produces a clear response. It’s difficult to get a reading from his second ear so Allison will be back later that day to repeat the test.

Mum Pauline Szyc with newborn son Mason Suddaby

Along the corridor, Paulina Szyc cradles son Mason Suddaby in her arms while Allison fits the ear piece.

All screeners have “quiet please, hearing test in progress” signs attached to their trolleys to pin on the outside of doors. But in a busy ward environment, silence is not always possible.

It’s one of those days today. Like Frederick Thomas, Allison can’t get a response from Mason’s ears. She tells Paulina she’ll be back.

When babies are tested so early, a lack of clear response is a common problem. While it might make sense to carry out the tests later once birth fluid has subsided, there are concerns more babies would go untested as some mums would be unlikely to return to hospital for a further appointment. Also, it could cause a delay in diagnosing a hearing problem.

“We try and make it as easy as possible for them and do it while they’re here,” says Allison. “We try to reassure them there’s unlikely to be anything to worry about but we need to make them aware of the need for the screening to take place.

“But, sometimes, there is something wrong and we need to prepare them for that, to put that possibility in their mind.”

When there is no response from the AOAE, a second screen known as an automated auditory brainstem response (AABR) is carried out. This time, sensors are placed on the baby’s forehead, neck and shoulders.

Tiny headphones are placed over the baby’s ears while gentle clicking sounds are played in a screening test lasting anything from five to 15 minutes.

Results are given to the mother as soon as the test is completed. If clear responses are not given for one or both ears, the baby is referred to audiology for more in-depth tests within four weeks.

The swift turnaround means babies as young as eight weeks old can be fitted with hearing aids.

It’s an essential service but the team realised some women were not aware of its importance so two members of the team now attend the monthly Hey Baby Carousel events at the hospital to explain their work to expectant mothers and fathers.

Allison says: “The important thing for us is good communication with the mums. It is important for us to communicate our message and show why their baby needs this.

“And if there are problems, it’s better to know.”