He remembers the date he walked into Alderson House – December 7, 1981. Press him and he’d probably know the time.

That’s the thing about Chief Nurse Mike Wright – he likes detail.

Back then, it was the Hull District School of Nursing when the boy from a working-class family in East Hull joined a group of 40 training to become nurses.

The circle will complete when Mike Wright walks out those same doors next March for the last time to begin his early retirement after 37 years, reaching the highest levels of his profession.

In his office on the first floor of the building where he started his nursing career, the words of Senior Tutor Ivy Harrison – a towering, formidable figure and a delightful lady with her royal blue belt, starched hat and court shoes – echo down the corridors of time.

“She told us ‘Welcome to the greatest profession in the world,’” says Mike. “I look back now and wonder was she right?

“For me, she was.”

Mike, 55, embarked on his nursing career after gaining eight ‘O’ levels from Andrew Marvell School.

“My parents and my grandparents, all of them were grafters,” he said. “They were hard-working people. We weren’t poor but we were never rich. We just had a good life, we were treated well and we were loved.

“I was always taught never to spend money you didn’t have, always be courteous and polite to people, never cheek your elders and take your shoes off when you go into someone’s house.”

You see the boy in the man and that strong work ethic runs through him. There are few nursing tasks, if any, Mike hasn’t done.

His career is punctuated by examples of when he’s rolled up his sleeves, regardless of his job title.

Ever an eye for forensic detail, Mike originally intended to join the police or go into law but chose nursing after his cousin and wife, both nurses in the Australian outback, came home to visit. They convinced him it was a great life. “They were right,” he says.

First qualifying in March 1985, he was a Staff Nurse in Neurosurgery and Neurosurgical Intensive Care at Hull Royal Infirmary before shifting to General and Vascular Surgery. Back then, nurses were encouraged to build up their skills in different areas and Mike applied to all 20 centres offering the ENB 100 general intensive care nursing programme. Gaining a place was extremely rare in those days.

He was interviewed at Guy’s Hospital in London, offered a place immediately. And that’s something else Mike does – he seizes opportunity.

He arrived in London in October 5, 1987, chuckling at the memory of his sister and her husband unloading his possessions from the back of their estate car and leaving him in the less-than-glamorous nurses’ residence. “I found out later she cried on the way home because she’d to leave me there,” he says.

Mike soon got a taste of life working in a busy hospital in central London five weeks later when fire swept through King’s Cross Station, killing 31 people.

It was the first of five major incidents or terrorist attacks he was to become involved in during his 18 years in London – Kings Cross, the Clapham rail crash, the Marchioness Disaster, the London Bridge Bombing by the IRA and the Soho Pub Bombing.

He carries memories of them all. But two – the Marchioness Disaster and Soho – haunt him.

Fifty-one people died when the pleasure cruiser Marchioness collided with the Bowbelle dredger in 1989.

Mike was charge nurse on night shift and remembers how staff, based yards away from the Thames, first knew something terrible had happened when survivors, dripping wet, started walking through the doors of Guy’s Hospital A&E after swimming for their lives.

People had bony injuries caused by the crash, hypothermia and some had to be treated for Leptospirosis or Weil’s Disease after swallowing contaminated river water.

And he remembers families, searching desperately for relatives. The ones left at the end were those whose loved ones were still on the pleasure cruiser, sunk beneath the Thames.

A decade later, he was just driving into the Tesco car park at Lewisham when he heard on the radio about an explosion outside the Admiral Duncan pub in Soho on a Friday night in April 1999. Three people were killed and more than 80 were injured when a neo-Nazi planted a nail bomb and some of the victims were brought to Guy’s and St Thomas’s Hospitals.

“They had the most horrific injuries,” Mike says. People lost limbs, some had six-inch nails embedded all over their bodies, others had terrible burns caused by the force of the blast.

Then Directorate Manager and Head of Nursing for Anaesthesia and Theatre Services, it was all hands to the pump.

“We didn’t have enough people to look after ventilated critically injured people and I hadn’t looked after a ventilated patient for about five years but I had to take a patient myself,” he says. “You wonder if you’ll remember how to do it. But I did and it all came flooding back.”

He also remembers the following day travelling in the back of an ambulance with a student nurse to transfer another badly injured patient from the bomb to a specialist burns unit.

“All of these things make you realise no-one ever wants to be in hospital,” he says. “Our job is to try and make sure we look after you and despite the difficulties, preserve your dignity and treat you as an individual.”

Those extreme moments made him appreciate the NHS – and the people and teams who work for it – even more.

Ultimately, he spent 18 years down south, working his way up from Staff Nurse in General Intensive Care to the lofty heights of Executive Nurse Director at Bromley Hospitals NHS Trust in Kent.

He came back to Hull in October 2005, first as Executive Chief Nurse and Deputy Chief Executive, and then again as Executive Chief Nurse in April 2015 after a two-and-a-bit-year stint as Executive Director of Nursing and Patient Experience at County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust.

“I never set out to be Chief Nurse,” he says. “It’s not something you walk up one day and say that’s what you are going to be.

“It’s just that all of my jobs have come along when the circumstances meant I was in the right place at the right time.”

He’s always been prepared to learn, to have the drive and commitment to fill in the gaps in his knowledge as he climbed the career ladder. He undertook a Masters degree in Business Administration, honing his understanding of finance because he knew he’d need it.

“I have always tried to seize the opportunity and turn it into a positive,” he says.

“I have gone through my life developing my career. It has a clinical underpinning but I didn’t have strategic leadership experience.

“My last job at Guy’s and St Thomas’ was as Deputy Chief Nurse and that taught me how to hone my negotiating, influencing and facilitation skills. This was the first time I had stepped away from directly line managing large groups of people but this then gave me the taster to becoming a chief nurse.

“In this role, you have to influence people so it requires softer negotiating skills and you encourage rather than instruct.”

During his time in Hull, he’s won national recognition for introducing fundamental nursing standards on every ward and introducing safety briefings five times a day where the acuity of patients is balanced against available staff. The patient remains at the core of everything Mike Wright does.

And it always will, despite modern ways of nursing and new technology.

For new nurses starting today, he has these pearls of wisdom.

“The fundamentals of patient care remain the same as does the essence of nursing and midwifery care – the ability to understand your patient, how they are presenting to you and what they are saying to you,” he says.

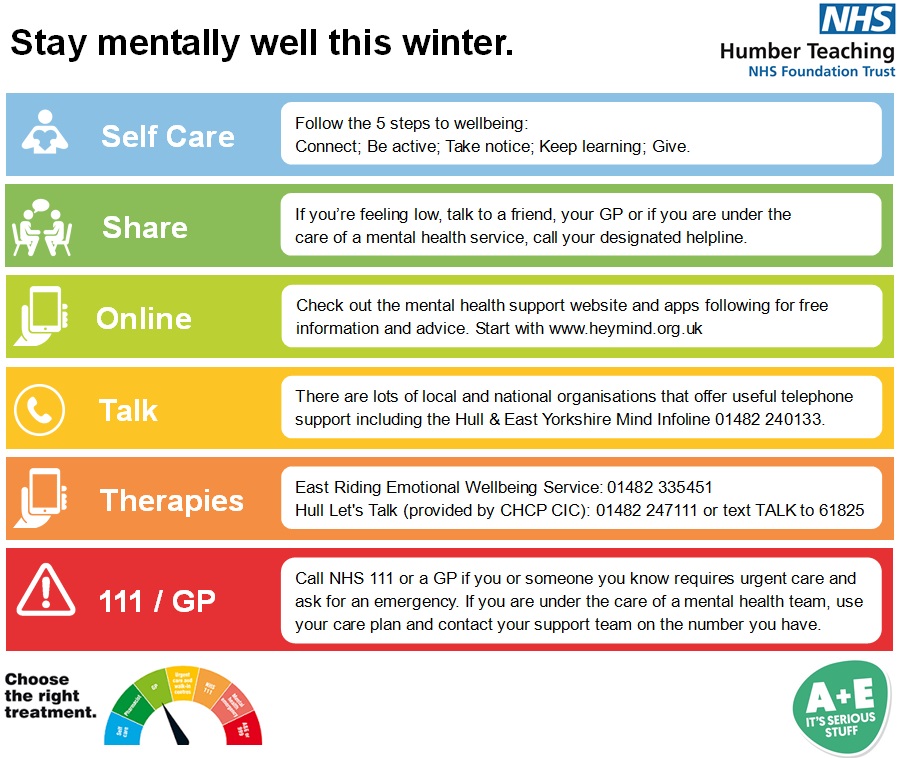

“Yes, use technology but don’t lose the human skills of assessing, listening and understanding what the signs are showing you. No technology in the world can replace that. There is always the intuitive sixth sense, which you can’t write down on a piece of paper.

“And always be compassionate – even if you don’t know what it feels like for that patient, imagine what it feels like to be them and think about how you would like you or a member of your family to be treated.

“Don’t lose sight of the part you play in supporting patients through some of the darkest and most difficult moments of their lives. They are vulnerable and they trust you. You must never deny them that trust.”

He’s got big plans for his retirement. This is Mike Wright, of course he has. He’s going to America for a month, seeing friends, travelling Route 66 and snow-trekking and seeing the Northern Lights in Alaska. He’s planning to travel the world seeing friends.

But it’s hard, if not impossible, to imagine Mike outside of nursing. It’s been a lifelong passion and it’s likely to remain so.

He’s planning consultancy work, helping other trusts tackle nursing issues and other thorny issues, and, free from the constraints of working within the NHS, he’s set to share his views.

He makes no bones about the need for investment in training and is desperately worried about the shortage of registered nurses.

“As a trust, we’ve started to make inroads with the nursing apprenticeships and Nursing Associates but this is a national issue,” Mike says.

“How this is going to be corrected will continue to be a source of anxiety for me and I will continue to do what I can to influence that once I have left. There’s so much more to do.

“I see nurses and midwives as national treasures. You get paid to train as a police officer or in the armed forces and you’re paid to train as a fireman. But you’re not paid to train as a nurse or a midwife and I think that’s going to have to change.”

When he walks out the door for the last time, he knows it’s the NHS team he’ll miss the most.

“It’s been a massive privilege to serve patients,” he said. “I’ve learned so much from them. I’ll miss being part of fantastic clinical teams. You come together and the team work, that dynamism and the skill of people astonishes me. There’s nothing quite like it and I’m so lucky to have worked with and learned from such amazing people. I’d like to thank them all.”

“I’m just really pretty humbled by the fact that I’ve had the chance to do all of this.”