- Reference Number: HEY1084/2023

- Departments: Neonates

- Last Updated: 30 November 2023

Introduction

This leaflet has been produced to give you general information. Most of your questions should be answered by this leaflet. It is not intended to replace the discussion between you and the healthcare team, but may act as a starting point for discussion. If after reading it you have any concerns or require further explanation, please discuss this with a member of the healthcare team.

What is Retinopathy of Prematurity?

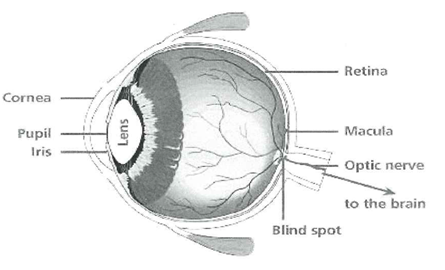

The retina is the light sensitive surface at the back of the eye. It converts images into nerve signals that the brain can understand. In the womb the retina develops slowly and the retinal blood vessels only complete growing when a baby reaches full term. If a baby is born early these blood vessels can grow abnormally which can cause damage to the retina. This is called Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP). ROP affects around 20% of babies who are premature. It mainly happens in babies who are born less than 31 weeks gestation or weigh less than 1500 grams (1500g) at birth.

Why does a baby need ROP screening?

ROP is not passed from parents to children. It happens because a baby is born too early for the retinal blood vessel to grow. These blood vessels that supply blood to the retina usually develop between 16 and 36 weeks. They are needed to provide a continuous supply of oxygen to the retina. If a baby is born before the growth of these blood vessels is complete, there will be areas that do not receive enough oxygen.

This causes chemicals to be produced to make new blood vessels. Because they are very fragile they can leak blood which can cause scarring/permanent damage to the retina and sight.

Premature babies often need oxygen especially if their lungs are not yet fully formed. Oxygen levels are monitored very carefully in these babies because too much oxygen can be harmful for the production of healthy blood vessels.

Can there be any complications or risks?

Some babies react to having eye drops and may have a fall in their oxygen saturations.

How do I prepare for the ROP screening?

Each baby needs to fit a certain criteria to be eligible for ROP screening. It is part of the doctor’s role to identify each baby who will have ROP screening. There is a nurse who as the ROP coordinator helps to ensure the babies screening takes place. Parents/carers will be informed when their baby is to be checked and asked to give their verbal consent.

What will happen?

There will be no obvious signs that a baby has ROP. It needs an eye specialist (Ophthalmologist) to look into the eye with a light and magnifying lens to see into the eye. Babies who fit the criteria will be screened every one or two weeks to closely monitor for signs that the baby is developing ROP.

Before the eye examination eye drops will be used to dilate the pupil. The ophthalmologist will use a head mounted ophthalmoscope which lets him see inside the eye with a magnifying lens. Sucrose (sugar water) can be given to soothe the baby as needed. Sometimes equipment is used to open the eye wider and/or put pressure on the eyeball to help get a better look. Anaesthetic eye drops are used to make it more comfortable for the baby if this equipment is used.

What will happen afterwards?

Most babies have mild ROP. If this is the case they will not need treatment and it will get better by itself. It will not affect their vision. However at its worst ROP can cause total blindness. This is why it is very important that babies are monitored closely and the treatment is given as soon as possible.

There are 5 stages of ROP. The ophthalmologist will talk to parents and explain should he have any concerns. Treatment is available, the most common being laser surgery which can be carried out on the neonatal unit. Babies who need this treatment will need to be re ventilated as they will need a general anaesthetic for the surgery.

Should you require further advice on the issues contained in this leaflet, please do not hesitate to contact the Neonatal Department on tel: 01482 604391.

General Advice and Consent

Most of your questions should have been answered by this leaflet, but remember that this is only a starting point for discussion with the healthcare team.

Consent to treatment

Before any doctor, nurse or therapist examines or treats your child, they must seek your consent or permission. In order to make a decision, you need to have information from health professionals about the treatment or investigation which is being offered to your child. You should always ask them more questions if you do not understand or if you want more information.

The information you receive should be about your child’s condition, the alternatives available for your child, and whether it carries risks as well as the benefits. What is important is that your consent is genuine or valid. That means:

- you must be able to give your consent

- you must be given enough information to enable you to make a decision

- you must be acting under your own free will and not under the strong influence of another person

Information about your child

We collect and use your child’s information to provide your child with care and treatment. As part of your child’s care, information about your child will be shared between members of a healthcare team, some of whom you may not meet. Your child’s information may also be used to help train staff, to check the quality of our care, to manage and plan the health service, and to help with research. Wherever possible we use anonymous data.

We may pass on relevant information to other health organisations that provide your child with care. All information is treated as strictly confidential and is not given to anyone who does not need it. If you have any concerns please ask your child’s doctor, or the person caring for your child.

Under the General Data Protection Regulation and the Data Protection Act 2018 we are responsible for maintaining the confidentiality of any information we hold about your child. For further information visit the following page: Confidential Information about You.

If you need information about your child’s (or a child you care for) health and wellbeing and their care and treatment in a different format, such as large print, braille or audio, due to disability, impairment or sensory loss, please advise a member of staff and this can be arranged.

Your newborn baby’s NHS number

An NHS number is allocated to everyone whose birth is registered with a Registrar of Births and Deaths in England and Wales. You already have an NHS number and your baby will be assigned an NHS number soon after birth. Your NHS number is unique to you and provides a reliable means of linking you to the medical and administrative information we hold about you. NHS numbers are allocated on a random basis and, in themselves, provide no information about the people to whom they relate.